Let’s save the world!

This is the first in a series about saving the world. I am neither exaggerating nor kidding. The bad news is that the world needs saving. The good news is, you are in a perfect position to save it.

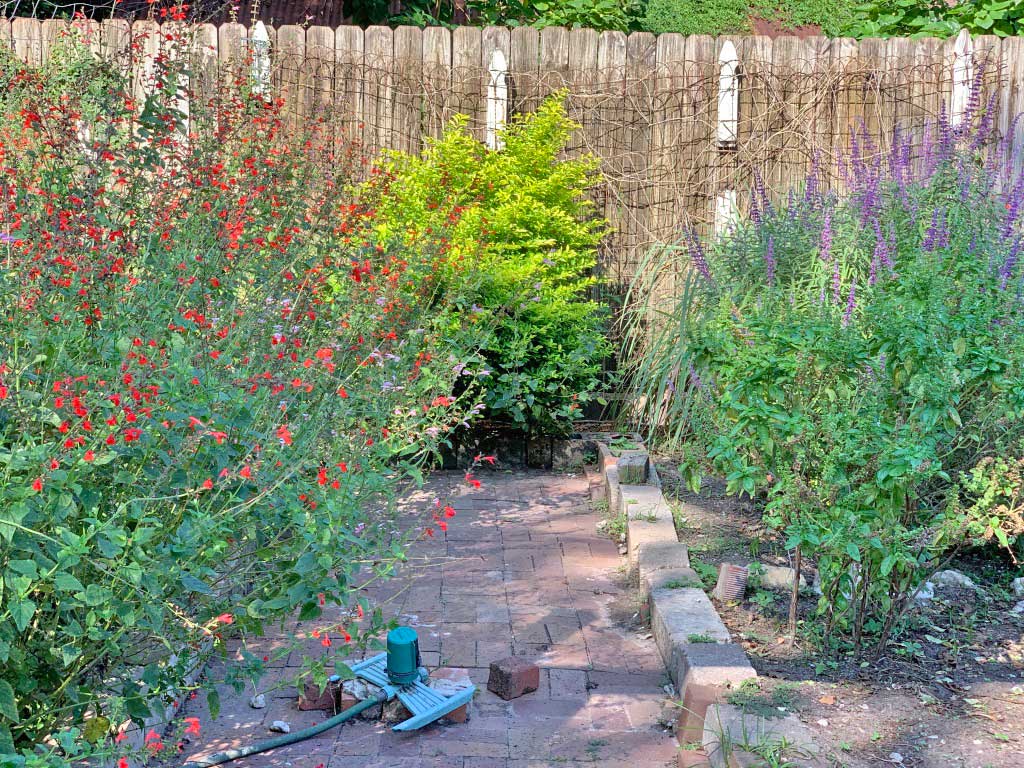

In this first installment, I will introduce you to two plants currently making their debut in the small, private nature preserve I manage. Each has come into flower for the first time this fall.

The first is Mexican bush sage (Salvia leucantha.) It is a lovely plant that has been represented in the preserve on and off for many years. The current crop (which was purchased from a big-box store) was planted during the late spring and came into glorious full flower last month.

The Mexican bush sage is the purple plant on the left.

The second is a fragrant mistflower (Chromolaena odorata). This is an unruly fall-blooming native that is considered a pest everywhere outside it’s natural zone, which, luckily, includes here. I call it unruly because it will be a shrub before you know it and it produces abundant seeds. I acquired it from Morning Star Prairie Plants, run by a fellow master naturalist, Mark Morgenstern.

The fragrant blue mistflower is the plant covered in monarch butterflies.

Both of these plants are show-stoppers. Only one of them produces flowers.

What is a flower?

This seems the sort of question that appears on a quickie dementia test where they make sure you can still tell a clock from a camel. But that question has become oddly complicated. And don’t you know it’s our fault.

Using the first definition the Google provides, a flower is the seed-bearing part of a plant, consisting of reproductive organs (stamens and carpels) that are typically surrounded by a brightly colored corolla (petals) and a green calyx (sepals).

Our bush sage meets those criteria. I even pulled one apart and put it under a microscope to make sure. But I still contend that it does not produce flowers. I have it on good authority. The bees told me.

This microscopic view of the Mexican bush sage bloom shows anthers that seem to have pollen and the larger structure in the middle is the female reproductive component. Sure looks flower-like.

I didn’t realize right away that the bees were completely ignoring the Mexican bush sage (Mbs). But once I noticed, it was not subtle. The plants right next to Mbs were humming with bees; the Mbs was getting as much attention as lawn furniture.

There are a couple of things that might cause pollinators to ignore a flower. One of them is that the flower might not want them. This sounds kind of weird, but plenty of plants specialize in a particular pollinator and they make it hard for others to get anything. Later in this series, we will discuss this sort of thing in detail. But I know from experience that Mbs is an all-purpose pollinator.

So how did I come to have a plant on the preserve that was apparently invisible to pollinators? Unfortunately, this not being my first rodeo, I had a very good idea what had happened. I had purchased a cultivar that was somehow incomplete.

You may not realize it, but we now have a two-track system for flower development. The first is the one that has been in effect since the beginning of time.

System One: The old-fashioned way

Plants need insects for reproduction. Hard to breed if you can’t move around. So plants make use of those highly mobile insects. They lure them in with free sugar water that plants can make from nothing more than the soil they stand in and the sun that shines upon them. While the insects are feasting, they more or less inadvertently collect pollen from one plant and deposit it on another.

Plants and insects worked out this first system in partnership, and continuously road-test and improve it in a process that has been in place since time began. The shorthand way to refer to this is evolution.

This is a honeybee on fragrant blue mistflower. Notice how many flowers are contained in that small bloom. I decided to stop counting after a dozen. Each one of those is a nectar source and those wavy things coming out of the flower are the pollen bearing parts. Hard to avoid when you are diving for that sugar water.

The second system produced my invisible plant.

System Two: The new way

Humans throughout time have bred one plant to another hoping for something “better.” Not a big problem when we were out there like Gregor Mendel breeding one type of pea to another and deducing genetics. That’s because then, plants still required pollinators.

If Mendel or his successors bred one pea to another and the resulting pea plant produced no peas, there would have been no way and no reason to continue. Who wants peas with no peas?

But today, if that fruitless-pea had unusually large flowers that were startlingly fragrant, who cares about the fruit! Nurseries can manufacture seedless plants in perpetuity. People will stick them in the ground and be glad not to be cleaning up pods all summer. A cultivar is born.

A cultivar is a variety built by us. When we cultivate a plant, we decide to breed what to what in order to create a plant more pleasing or useful to us. That more useful variety is a cultivar.

As an example, apples are all in the genus Malus and many of the ones we like are of the species domestica. When we use Latin nomenclature, we call apples Malus domestica with the genus capitalized and the species lowercase; it is usually italicized. Apples have tons of cultivars that you know well, Macintosh, Red Delicious, Jonnagold. In Latin, a Macintosh apple would be Malus domestica “Macintosh.” The cultivar isn’t italicized and is usually in quotations. Nature produces species, humans produce cultivars. Still, nothing terrible going on. In theory.

But we have a problem on our hands. Plants have spent eternity working out complicated signaling systems to draw insects to them. I promise I will entertain you with the details in coming posts. But, when we breed plants to draw humans rather than insects, we sometimes, accidentally, erase the signals. Or we change the nectar so it is no longer palatable or even present. And we have no idea that we’ve done it. We don’t see in the UV spectrum. But butterflies and bees do. They rely on signals in this spectrum to even find flowers. After we are children, we usually stop pulling flowers apart for the sweet part. But that’s what feeds a huge percentage of the insect population.

If nature makes changes that turn plants invisible or unpalatable, the resulting plant won’t last. To be successful, a plant needs to attract someone to help with sex and then reward them for bothering. If a plant suffered a mutation that erased its signaling ability, not a single pollinator would show up and not a single seed would be set and this mutation would last only a single generation.

I love how you can see the body of the monarch flexing as the wings beat downward.

All of life presently on earth springs from the deal that plants made with insects before time began. It is the foundational agreement of our world. Everything depends upon it. And we have broken it.

We have filled the world with cultivars that look exactly like the plants they sprung from. In fact, they look better. They were designed to produce in you a burning desire to put this plant in your own small private nature preserve.

Plants that don’t feed pollinators may sound like a technical thing that only a nature nerd would care about. Before the world lost 75% of the biomass of flying insects, I might have agreed. But we have, and what you do makes a difference. See the insect rant. Really. I’ll wait.

The commercial nursery industry didn’t set out to create invisible plants. But they have. There is a type of jasmine that is placed on every fence of every townhome near the preserve. I have a standing offer of $5 for any photo of a bee on one of these vines. (I have never seen one and I am hereby limiting this challenge to the first 10 photos in case I’m just very wrong about this!)

On the left is a local cultivar I named Salvia greggii “Lilliana B.” It is a salvia that beloved by every pollinator that passes by. It is the workhorse of the preserve. It springs up everywhere, grows to enormous size before you know it, blooms constantly and sets abundant seeds. Lilliana is for our street and B is for backyard. The Lilliana in the front yard is pink and is named Salvia greggii “Lilliana F.” Both were produced by the old method; every salvia we ever dragged home from a nursery, bred together over time to produce these consistent cultivars. On the right is the Mexican bush sage Salvia leucantha “some cultivar.” It was bred because it is gorgeous. It never sets any seeds because it is never pollinated.

There are over a million single-family homes in Harris County. At almost every one of them, the occupants have put plants in the ground. Probably cultivars developed to please someone not a pollinator. Estimating based on a land-use chart, residential real estate occupies over 80% of Harris county.

So, on 80% of the land in Harris County, bees are starving and no one is doing anything about it. No one even notices.

Job One: Start noticing

So here is your first job in saving the world. Start noticing. Notice in your own yard. You, too manage a small private nature preserve. You might not think of it that way, but in Harris County, 80% of nature is in private hands. Are you doing well at management? I know many have to balance the requirements of HOAs, but at minimum, you should make sure the plants you put in the ground are feeding someone. If they are not, rip them out and put in new ones.

If you want an example of what the insect activity in your yard should look like, wander by any weedy lot and watch. If you can’t even beat a weedy lot, you should be embarrassed.

The fact that I acquired and let flourish almost completely useless plants for months lets you know that the job isn’t easy. By the way, the plant persists on the preserve because something very interesting happened and that will be the subject of next week’s post.

For now, look for cultivars. And avoid them. You know something is a cultivar because in addition to the italicized latin names for the Genera and the species, there will be another word, probably in quotes and probably sounding like marketing. Avoid anything with a marketing word. It is not guaranteed to be useless, but it might be.

A good way to make sure you are buying plants that were built by and for insects is to buy plants from nurseries that grow out wild-collected seed. Master naturalists collect seeds from vestigial prairies so as to conserve the plants that were made the old-fashioned way. Those seeds are propagated by Native American Seed. You can buy seeds from them.

Nurseries that specialize in growing plants from wild-collected seeds include The Houston Audobon Natives nursery and Morning Star Prairie Plants.

That fragrant mistflower that started blooming a few weeks ago is so full of magic, I cannot believe. That’s what genuine, pollinator-bred plants can do. It is never without butterflies and bees. With a few plants such as this to anchor a preserve, you could even dare to indulge in a few showy ornamentals. But when people ask how you get so many bees and butterflies, don’t you dare point to those show-pony cultivars!

If you know some local nurseries who grow from wild-collected seeds, please let me know. I will keep a link to what I hope will be a growing list of resources. Please contact me with suggestions.